FactualFor two years, the photographer Ricardo Nagaoka followed the African Americans of this Oregon city, chased out of their historic district by gentrification. And portrayed those who, even more than their homes, have lost a part of themselves.

In contemporary America, the city of Portland, Oregon, is known for its progressivity, its cultural scene and its commitment to the environment. But the photographer Ricardo Nagaoka shows a completely different side of reality. He is interested in the African American community of the city, in its history, in all its complexity. He who was born in Paraguay to Japanese parents and made Oregon his homeport describes the historic black population district, northeast of Portland, and how this small community – only 6% of the few 600,000 inhabitants – is marked by the white supremacist past of the city.

Supremacism and Ku Klux Klan

When the state was created in 1859, the Constitution forbade blacks not already residing in Oregon to join Oregon, making it the only "white only" state in the Union. Over the decades, segregation has become embedded: the state has ratified the fifteenth amendment to the American Constitution – introduced in 1870, it gave the right to vote to black men – in 1959; the Ku Klux Klan flourished at the beginning of the XXe century and a supremacist community developed there until the 1990s.

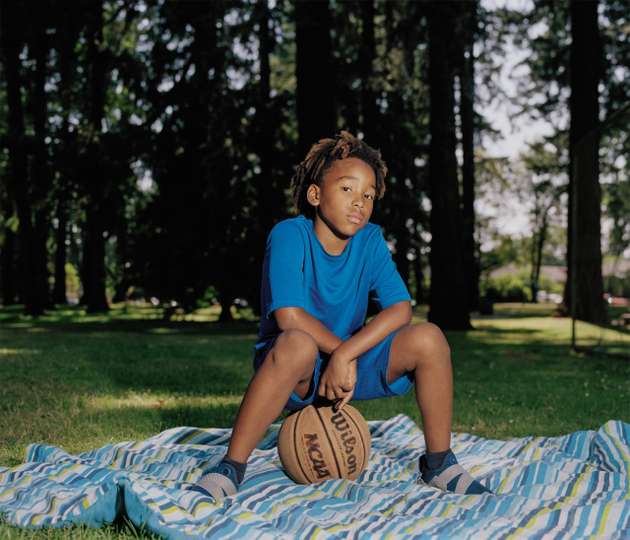

Here, even the children seem to have put away their smile.

Nourished by this particular context, Ricardo Nagaoka followed for two years the population of this district. This has been forced by the rise in housing prices, the lack of tenant protection and the gentrification of the city, to abandon homes to developers. "This phenomenon exists in other cities of the United States, but here it is particularly fast. Some families have seen their rent increase from $ 300 to $ 500 a month for a year, explains the photographer.

In the portraits that populate this project – and future book – entitled Eden within Eden, title borrowed from a book by James J. Kopp devoted to the utopias that emerged in this state, Nagaoka seized "Sadness and frustration" inhabitants. Here, even the children seem to have put away their smile. "Originally, these people were forced to live together in parts of the city; they built their house, their world, and today they are forced to leave, to disperse in peripheral areas. "

"When you lose your home, it's not the physical loss of the rooms that we feel, but the memories and identity that we have forged in those places. Ricardo Nagaoka

Those who remain are regarded as strangers: "We make them understand that their place is not really there. But even if their streets were also hit by drugs or gang violence, it was the only place they could say: it's my home. " But the photographer, himself uprooted from Paraguay to Canada, then to the United States, preferred to stop on faces rather than on lost homes. "When you lose your home, it's not the physical loss of the rooms that we feel, but the memories and identity that we have forged in those places. I did not want all these people to be reduced to statistics, but to tell their story. "

The clichés, however, stop at some of the most emblematic places in the neighborhood and the "life before": the Baptist Church, which was one of the first places of African-American worship in the city and saw the birth of the local movement for civil rights, the park where the locals meet with their families. Nagaoka testifies: "Even moved to the other end of the city, they come back to church on Sunday to find the meaning of their community, or in the park where they played as children. "